Public awareness campaigns are one of the most common tools governments and public institutions use to influence public outcomes—health, safety, environmental protection, civic participation, service uptake, and more. They are also one of the most misunderstood.

Many campaigns achieve what looks like “success” on paper: big reach, high impressions, strong media coverage, a viral video, a well-attended launch event. And yet, when you look for the outcome that mattered—understanding, uptake, compliance, or behavior change—nothing meaningful shifts.

That gap is the public awareness paradox: a campaign can be highly visible and still be ineffective.

This article explains why so many public awareness campaigns fail, what those failures cost, and how governments can design campaigns that actually work—strategically, ethically, and measurably.

What Is a Public Awareness Campaign?

A public awareness campaign is a structured communication effort intended to influence public knowledge, understanding, attitudes, or behavior related to a public issue or policy.

Governments typically run awareness campaigns to:

-

inform citizens about a risk or issue (dengue prevention, road safety, air pollution)

-

explain a new policy or reform (new registration system, tax changes, public service processes)

-

encourage participation (vaccination, school enrollment, disaster preparedness)

-

reduce harmful behaviors (drunk driving, littering, unsafe construction)

-

improve public cooperation (water conservation, reporting guidelines during outbreaks)

Public awareness campaigns can be short bursts or multi-month programs, but the key is that they aim to create change at scale.

Awareness vs impact: the mistake that kills effectiveness

Awareness is not a single thing. It is a ladder:

-

Awareness — “I’ve heard of this.”

-

Understanding — “I know what it means and what it asks of me.”

-

Belief/Trust — “I think it’s true and worth acting on.”

-

Intent — “I plan to do it.”

-

Action — “I did it.”

-

Sustained behavior — “I keep doing it.”

Many campaigns stop at step 1 and call it success. But most public mandates require movement further up the ladder—especially when behavior change is involved.

Why Public Awareness Campaigns Fail

Campaign failure is rarely about “bad design” alone. It’s usually about strategic misalignment—between the goal, the audience, the message, the channels, and the real-world conditions required for change.

Below are the most common failure points.

1) Confusing awareness with behavior change

A campaign may tell people what to do, but behavior is shaped by:

-

convenience and access

-

cost and time

-

fear and stigma

-

habit and social norms

-

trust in the messenger

-

competing daily pressures

If a campaign assumes information alone will shift behavior, it will often fail.

Example pattern:

People know smoking is harmful; many still smoke. People know speeding is dangerous; many still speed. Knowledge doesn’t automatically translate into action.

What works instead: design for the real drivers of behavior—friction, incentives, norms, trust, and practical barriers.

2) No clear, measurable objective

“Raise awareness” is not a measurable objective. It’s a vague activity.

A campaign needs a specific outcome statement, such as:

-

Increase correct understanding of X from A% to B%

-

Increase registrations/enrollments by X%

-

Reduce instances of Y behavior by X%

-

Increase hotline calls/clinic visits/reporting by X%

-

Increase compliance with a specific guideline

When objectives are unclear, everything else becomes guesswork:

-

messaging becomes scattered

-

creative becomes decorative

-

channels are chosen by habit

-

measurement becomes vanity metrics

What works instead: one primary objective, one primary audience, and a small number of supporting indicators.

3) Poor audience understanding

“The public” is not a single audience.

Different groups may:

-

have different beliefs and misinformation exposure

-

face different access and affordability constraints

-

have different language needs

-

trust different messengers

-

have different reasons for not acting

When campaigns treat everyone the same, they often persuade no one.

Common symptom:

A campaign addresses the needs of high-information, high-trust, urban audiences—while the people most affected by the issue remain unreached or unconvinced.

What works instead: segmentation based on behavior and barriers, not only demographics.

4) Message overload and complexity

Public institutions often communicate like institutions: formal, detailed, policy-heavy.

But public attention is limited. People need:

-

simple framing

-

a clear “why”

-

a clear “what to do”

-

a clear “where to go for details”

Campaigns fail when they:

-

contain too many messages at once

-

use technical language

-

bury the action step

-

ask people to think too much before acting

What works instead: one core message, supported by short, practical guidance and FAQs.

5) Wrong channels for the audience

Campaigns often default to:

-

social media because it is trendy

-

TV because it feels “national”

-

press coverage because it signals credibility

But the right channel depends on:

-

where the audience actually pays attention

-

which sources the audience trusts

-

what access constraints exist (data costs, connectivity, device usage)

-

whether the desired behavior is urgent or sustained

Common failure: a digital-first campaign for an audience that primarily relies on radio, community leaders, or in-person networks.

What works instead: choose channels based on trust and access, then integrate them.

6) Lack of credible messengers

In low-trust environments, institutions may not be the most persuasive voice—even if they are the most authoritative.

Campaigns fail when the messenger lacks credibility with the audience.

What works instead: identify trusted messengers such as:

-

health professionals

-

teachers and schools

-

religious/community leaders

-

local authorities and frontline staff

-

peer groups and respected cultural figures

-

relevant influencers (when chosen carefully and ethically)

The messenger is often as important as the message.

7) Campaigns detached from reality

Communication cannot compensate for a broken system.

Campaigns fail when they promote a behavior that people cannot realistically perform because:

-

services are inaccessible or unclear

-

supplies are unavailable

-

processes are confusing

-

costs are too high

-

the “how” is not operationally ready

If the public tries to act and hits friction, trust declines—not only in the campaign, but in the institution.

What works instead: align communication with service readiness, ensure clear action pathways, and fix operational bottlenecks where possible.

8) No measurement beyond reach

Impressions, views, and media coverage are not impact.

Campaigns fail when measurement:

-

focuses only on output metrics

-

ignores understanding, sentiment, uptake, and behavior

-

lacks monitoring of misinformation

-

does not support iteration and adjustment

What works instead: measure what matters, learn fast, and adapt.

Why These Failures Matter

Public awareness campaign failures are not harmless. They create real costs:

-

Wasted public funds and donor scrutiny when results are not defensible

-

Policy resistance when people feel manipulated or confused

-

Missed public outcomes (health, safety, environmental compliance)

-

Long-term trust erosion when campaigns overpromise or feel disconnected from lived reality

-

Misinformation vulnerability when confusion leaves gaps others fill

Sometimes, an ineffective campaign is worse than no campaign—because it can reduce trust and increase cynicism.

The Strategic Role of Public Awareness Campaigns in Governance

When designed well, public awareness campaigns can be a powerful governance tool. They help governments:

-

support policy implementation and reform

-

encourage service uptake and compliance

-

establish clarity during uncertainty

-

reduce misinformation spread by providing consistent sources

-

build institutional legitimacy through transparency and responsiveness

The highest-performing governments treat awareness campaigns not as publicity, but as part of a broader public sector communications system.

How to Design Public Awareness Campaigns That Work

Effective campaigns are not built by starting with visuals or slogans. They are built by starting with outcomes and evidence.

Below is a practical framework governments can use.

Step 1: Define the real problem—and the specific outcome

Start with: What must change in the real world?

Replace vague goals with concrete outcomes:

-

“Increase proper waste separation in households in X district by Y%”

-

“Increase clinic attendance for prenatal visits by Y%”

-

“Increase correct understanding of eligibility rules by Y%”

-

“Reduce unsafe driving behavior in target segments by Y%”

If behavior change is required, define the behavior in plain terms:

-

who must do what

-

when and how often

-

under what conditions

A campaign without a defined outcome becomes a content exercise.

Step 2: Identify the audiences that matter—and segment them

There is usually:

-

a primary audience (the people whose behavior must change)

-

secondary audiences (influencers, family decision-makers, employers, community leaders)

-

implementer audiences (frontline staff, local officials, call centers)

Segment based on:

-

current behavior (already doing it vs not doing it)

-

trust level (high-trust vs low-trust)

-

barriers (cost, stigma, access, fear, misinformation exposure)

-

decision role (decision-maker vs influencer)

Segmentation should clarify which groups need different messages and messengers.

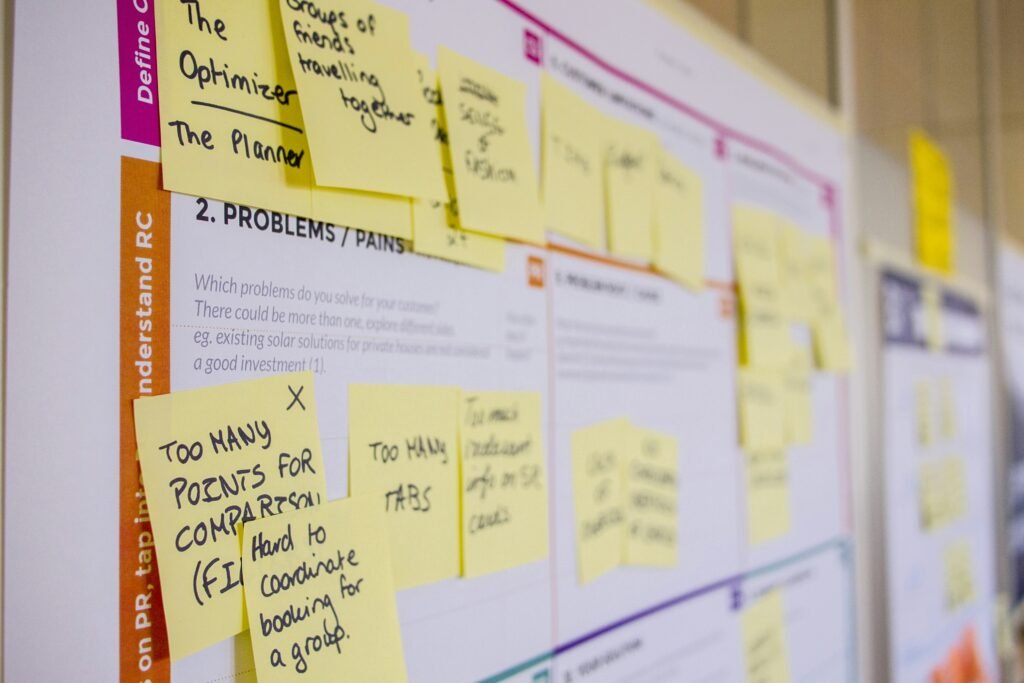

Step 3: Ground the campaign in insight, not assumptions

Gather evidence through:

-

rapid surveys

-

focus groups

-

stakeholder interviews

-

frontline staff feedback

-

digital sentiment listening

-

analysis of existing service data

You’re looking for:

-

what people believe now

-

what they misunderstand

-

what they fear

-

what would make action easier

-

who they trust

Most failed campaigns are built on internal assumptions rather than public insight.

Step 4: Apply behavioral science—make action easier

A strong public awareness campaign reduces friction and increases motivation.

Common behavioral levers include:

-

Simplification: reduce steps, reduce confusion

-

Prompting: reminders at the right time and place

-

Social norms: show that peers are adopting the behavior

-

Commitment: encourage public pledges or small first steps

-

Credible messengers: trust drives attention and belief

-

Loss framing: when appropriate, clarify risks of not acting

-

Immediate benefits: connect actions to tangible outcomes people care about

The most important rule: design for the reality of human behavior, not idealized rational behavior.

Step 5: Build message architecture—one core message, multiple supports

An effective campaign usually needs:

-

Core message: one sentence that frames the issue clearly

-

Reason/benefit: why it matters

-

Action step: what to do now

-

Practical guidance: where to go, how to access services, what to bring

-

FAQ layer: address confusion and common objections

-

Myth-busting layer: if misinformation risk is high

Use plain language. Avoid institutional wording. Test messages for comprehension with real audiences.

A simple test:

-

Can someone repeat your message correctly after hearing it once?

-

Can they explain the action step without confusion?

If not, simplify.

Step 6: Choose channels based on trust and access—and integrate them

Use channels for what they do best:

-

Mass media (TV/radio/OOH): broad awareness, legitimacy, repetition

-

Digital ads/search: targeting, optimization, rapid iteration

-

Social media: engagement, quick updates, rumor response

-

Community networks: trust transfer, hard-to-reach segments

-

Schools/clinics/frontline points: credibility at point of decision

-

Events/forums: dialogue, legitimacy, stakeholder alignment

-

SMS/WhatsApp-style messaging (where appropriate): direct reminders and urgent updates

Integration is crucial:

-

the same core message should appear across channels

-

different channels should reinforce different steps of the awareness ladder

-

owned platforms should act as the “single source of truth”

Step 7: Use credible messengers strategically

Select messengers based on:

-

audience trust

-

cultural relevance

-

expertise

-

reputation risk

-

consistency with the campaign’s purpose

Trusted messengers can include:

-

professionals (doctors, engineers, teachers)

-

local community leaders

-

peer champions

-

respected public figures

-

carefully chosen influencers (when appropriate)

This is especially important when institutional trust is low or when misinformation is active.

Step 8: Align communications with service readiness

Before launching, confirm:

-

Are the services actually available?

-

Are staff prepared to answer questions?

-

Is the website/portal updated and accessible?

-

Are helplines functioning?

-

Is there a clear pathway from message → action?

If not, fix readiness gaps or adjust messaging to avoid overpromising.

Awareness that leads to failed action attempts is a trust-destroyer.

Step 9: Measure what matters—and optimize in real time

A serious measurement plan includes:

Output metrics (basic):

-

reach, impressions, frequency, media coverage

Outcome metrics (essential):

-

understanding (short surveys, comprehension checks)

-

sentiment/trust indicators (qualitative + digital monitoring)

-

service uptake (registrations, clinic visits, hotline calls)

-

behavior proxy indicators (observations, compliance data)

-

misinformation tracking (rumor volume and spread)

Build feedback loops:

-

detect what’s not working early

-

adapt messages, messengers, and channels

-

document learning for future campaigns

Measurement turns campaigns from one-off spending into institutional capability.

Public Awareness vs Social Behavior Change Communication (SBCC)

Not all public issues require full SBCC. But many do.

Public awareness is often sufficient when:

-

the action is easy

-

trust is high

-

barriers are low

-

the goal is informational (e.g., eligibility rules, timelines)

SBCC is required when:

-

behavior is habitual or socially influenced

-

stigma, fear, or misinformation is present

-

barriers are structural (access, cost, social norms)

-

behavior needs to be sustained over time

Many campaigns fail because they were treated as awareness campaigns when they were actually SBCC challenges.

Public Awareness Campaigns in Emerging and Developing Contexts

In many emerging contexts, campaigns must account for:

-

unequal access to digital channels

-

language diversity and varying literacy levels

-

reliance on intermediaries (local media, NGOs, community leaders)

-

higher mistrust and political sensitivity

-

stronger influence of social networks and rumor spread

Design implications:

-

prioritize local insight and deep localization, not translation

-

include offline and community-based channels

-

use trusted intermediaries intentionally

-

build stronger listening mechanisms for early warning

-

design for inclusion—especially the people most affected by the issue

Conclusion: From Awareness to Impact

Public awareness campaigns fail for predictable reasons:

-

they confuse visibility with impact

-

they lack clear objectives

-

they don’t understand audiences deeply

-

they rely on complex messaging

-

they choose channels by habit, not trust and access

-

they ignore real-world barriers

-

they measure outputs, not outcomes

Campaigns that work are different by design. They are:

-

strategic and outcome-led

-

grounded in audience insight and behavioral realities

-

built on clear message architecture

-

delivered through integrated channels and trusted messengers

-

aligned with operational readiness

-

measured, optimized, and accountable

Public awareness campaigns succeed not when they are seen—but when they change understanding, behavior, and public outcomes.