Misinformation is no longer a side issue for governments. It shapes whether citizens trust public safety guidance, whether reforms are accepted, whether communities cooperate during crises, and whether institutions retain legitimacy. In many cases, the “real” event is quickly overtaken by the narrative about the event—and that narrative can be shaped by false or misleading information spreading faster than official updates.

Governments often respond to misinformation too late, too defensively, or in a way that unintentionally amplifies the falsehood. Others try to “fight misinformation” as if it’s purely a social media problem, focusing on takedowns and rebuttals while ignoring the deeper drivers: uncertainty, fear, low trust, and poor communication systems.

This guide presents a practical, public-sector approach. It explains what misinformation and disinformation are, why they spread so easily in government contexts, the real risks they create, and a step-by-step framework governments can use to manage information disorder while protecting public trust and democratic safeguards.

Why Misinformation Is a Governance Problem, Not a Media Problem

It’s tempting to treat misinformation as an online nuisance: rumors on social media, misleading posts, sensational headlines. But misinformation becomes dangerous when it affects public outcomes.

For governments, misinformation can:

-

reduce compliance with health and safety guidance

-

undermine crisis response coordination

-

trigger panic buying, mass anxiety, or social unrest

-

fuel backlash against reforms and public programs

-

erode trust in institutions, leaders, and public servants

-

increase polarization and societal division

-

cause reputational damage that persists for years

In other words, misinformation isn’t just about what people believe. It’s about what people do—and what they refuse to do. That makes it a governance and public safety issue.

Just as importantly, managing misinformation is not the same as controlling public opinion. Governments build resilience against false narratives most effectively by improving the quality, speed, and credibility of public information—not by attempting to suppress disagreement.

What Are Misinformation and Disinformation?

Clear definitions matter because different problems require different responses.

Misinformation

Misinformation is false or misleading information shared without intent to cause harm. People may share it because:

-

they believe it is true

-

it confirms existing fears or beliefs

-

it is emotionally compelling

-

it comes from a trusted friend or community group

-

they want to help others (“warning” behavior)

In many cases, the person sharing misinformation is not an “enemy.” They are a citizen acting under uncertainty.

Disinformation

Disinformation is deliberately false information spread to deceive, manipulate, or cause harm. It may be driven by:

-

political motives

-

economic incentives (clickbait, scams)

-

geopolitical strategies

-

extremist agendas

-

attempts to damage institutional legitimacy

Disinformation is often organized, repeated, and strategically timed—especially during crises, elections, or major reforms.

Related concepts governments encounter

Malinformation: true information used in misleading ways or weaponized through selective framing.

Example pattern: releasing a true statistic without context to provoke outrage or distrust.

Rumors and speculation: unverified claims that spread in information vacuums.

Rumors are not always malicious—but they can become dangerous quickly.

Conspiracy narratives: highly emotional explanations that thrive when trust is low and official information feels insufficient.

Conspiracies often resist fact-correction because they serve identity and emotional needs, not logic.

Why the difference matters

If governments treat all misinformation as hostile disinformation, they often:

-

respond aggressively and lose public trust

-

punish or shame citizens who are simply confused

-

escalate conflict and polarization

-

overlook the underlying gaps in official communication

A mature approach distinguishes between:

-

harmful, organized manipulation (disinformation)

-

confusion-driven rumor ecosystems (misinformation)

Why Misinformation Spreads—Especially in Government Contexts

Misinformation does not spread only because “people are irrational.” It spreads because conditions make it easy and rewarding.

1) Information vacuums and delayed communication

The fastest way to create misinformation is to remain silent when people are anxious.

When government communication is delayed:

-

citizens seek alternative explanations

-

rumor becomes a substitute for information

-

the first compelling narrative often becomes the dominant one

The rule is simple: if government doesn’t fill the information space, someone else will.

2) Low trust in institutions

Where trust is weak, official corrections are often rejected—even when true.

If people believe:

-

“government always hides things”

-

“officials lie to protect themselves”

-

“institutions don’t care about people like us”

then misinformation becomes more believable than official updates.

3) Complexity and uncertainty

Technical policies, scientific issues, and evolving evidence create confusion:

-

health risks

-

economic reforms

-

disaster projections

-

regulatory changes

Complexity creates cognitive overload. People prefer simple explanations, which misinformation often provides.

4) Emotional and identity triggers

Misinformation spreads faster when it triggers:

-

fear (“this will harm your family”)

-

anger (“they are cheating you”)

-

resentment (“this benefits elites”)

-

identity (“they are attacking our group”)

Emotion drives sharing. Facts rarely go viral without an emotional hook.

5) Digital amplification and media dynamics

Modern information systems reward:

-

speed over verification

-

outrage over nuance

-

repetition over accuracy

Algorithms and social networks amplify content that produces engagement. That makes emotional misinformation structurally advantaged.

The Real Risks of Misinformation for Governments

A. Public safety risks

Misinformation can lead to:

-

refusal of medical care or vaccines

-

adoption of dangerous “cures” or behaviors

-

disregard for evacuation warnings

-

panic buying and supply chain strain

-

stigma and scapegoating of communities

When misinformation affects safety behaviors, it is not just reputational—it is life-impacting.

B. Policy and reform failure

Reforms often fail because people believe:

-

costs are hidden

-

motives are corrupt

-

benefits are fake

-

the reform is foreign-imposed

-

the process is unfair

Even small misinformation claims can become a narrative that drives resistance, protests, and non-compliance.

C. Institutional legitimacy erosion

Repeated misinformation crises can create a long-term pattern:

-

official updates are not believed

-

every policy is interpreted cynically

-

institutions lose authority to coordinate action

Once legitimacy declines, governance becomes harder in every domain.

D. Escalation into crisis

Misinformation can transform manageable risks into full crises—especially when it:

-

triggers mass fear

-

fuels social tensions

-

spreads rapidly across regions

-

undermines emergency response cooperation

In modern governance, crisis communication and misinformation management are inseparable.

Common Mistakes Governments Make When Responding to Misinformation

1) Responding too late

Late corrections are often ineffective because the narrative has already hardened.

2) Overreacting and amplifying false claims

If government repeats the misinformation too prominently, it gives it additional reach. Many “debunks” accidentally serve as advertising for the rumor.

3) Using defensive or dismissive language

Statements like:

-

“this is fake news”

-

“the public should not believe rumors”

-

“people are spreading falsehoods deliberately”

can feel condescending and may reduce trust further—especially when citizens are genuinely anxious.

4) Treating all misinformation as malicious

Not all rumor spreaders are enemies. If governments respond as if citizens are attackers, they alienate the very people they need to reach.

5) Issuing complex, legalistic corrections

If corrections are full of jargon, people won’t understand them. Confusion invites misinformation to return.

6) Relying solely on fact-checks without trust-building

Fact-checks matter, but they are often insufficient in low-trust contexts. People need:

-

credibility

-

consistent updates

-

trusted messengers

-

clear actions

Core Principles for Managing Misinformation Effectively

Principle 1: Fill the information space early

Proactive communication reduces rumor growth. Early messages should include:

-

what is known

-

what is being verified

-

what people should do now

-

when the next update will arrive

Principle 2: Lead with credibility, not authority

Authority alone does not persuade. Credibility does.

Credibility comes from:

-

transparency

-

consistency

-

calm tone

-

evidence and clarity

-

acknowledging uncertainty responsibly

Principle 3: Be transparent about uncertainty

A key trust lesson:

-

Overconfidence destroys credibility when facts change.

-

Honest uncertainty builds credibility when updates evolve.

Use: “based on current information…” + “we will update at…”

Avoid: absolute statements that might not hold.

Principle 4: Correct without amplifying

The best practice is:

-

lead with the truth

-

keep the false claim minimal

-

repeat the correct information more than the rumor

-

provide a clear action and a credible source link destination (e.g., official portal)

Principle 5: Prioritize harm reduction over narrative control

Government’s goal should be:

-

protect public safety

-

enable correct action

-

reduce confusion

-

sustain trust

Trying to “win the narrative” can lead to aggressive tactics that backfire.

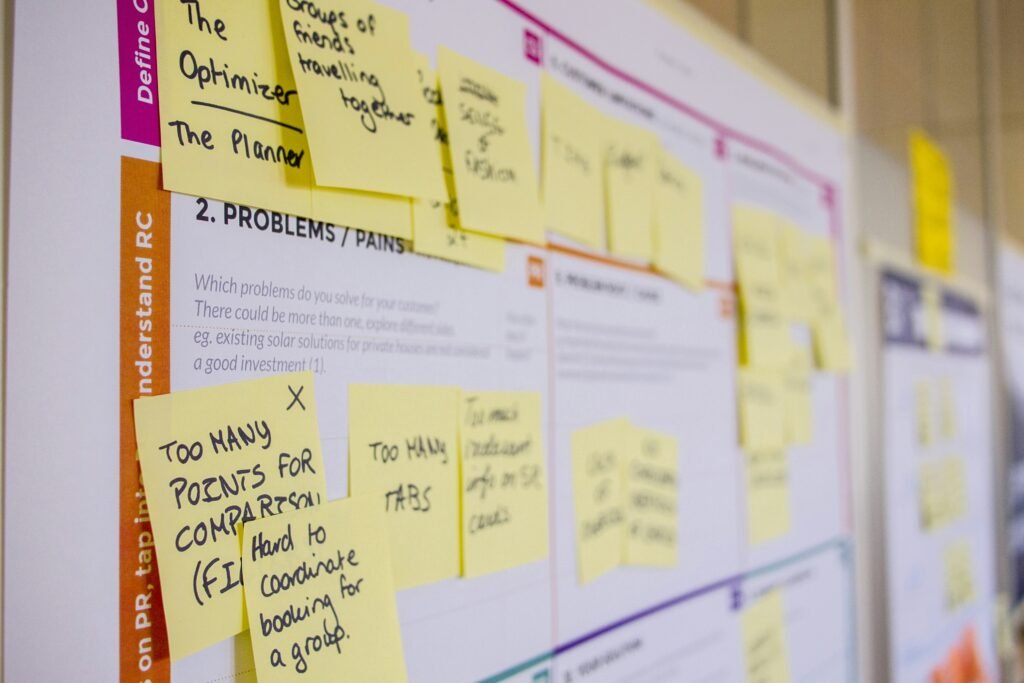

A Practical Government Framework for Managing Misinformation

Step 1: Identify and classify the misinformation

For every emerging claim, ask:

-

What exactly is being claimed?

-

Is it misinformation (confusion) or disinformation (intentional)?

-

Which audiences are seeing it?

-

Where is it spreading (platforms, communities, regions)?

-

How fast is it growing?

-

What harm could it cause (safety, trust, compliance, unrest)?

Not every rumor deserves a response. Response should be proportional to harm and spread.

Step 2: Assess risk and decide response thresholds

A practical triage model:

Monitor only when:

-

the claim is low reach

-

low harm

-

self-contained

Respond with clarification when:

-

the claim is spreading

-

causing confusion

-

likely to impact behavior

Escalate when:

-

the claim threatens public safety

-

may trigger unrest

-

undermines emergency response

-

targets vulnerable groups with hate or scapegoating

-

involves coordinated manipulation

Governments need clear thresholds so teams don’t debate endlessly while rumors spread.

Step 3: Establish a single source of truth

Create an official reference point:

-

a live-updated webpage or portal

-

verified social media channels

-

consistent update schedule (“updates at 10am and 6pm”)

-

a hotline or inquiry channel where possible

A predictable source reduces rumor dominance and gives media a reliable reference.

Step 4: Craft clear, audience-centered corrections

Good corrections should be:

-

plain language

-

calm and non-defensive

-

specific and actionable

-

short first, detailed second (layered information)

A strong correction structure:

-

The fact (truth)

-

What you should do

-

Where to get verified updates

-

(Optional) brief mention that false information is circulating—without repeating it excessively

Avoid insulting the audience. Focus on clarity and safety.

Step 5: Choose the right messengers

In low-trust settings, governments should not rely only on official spokespeople.

Use:

-

technical experts (health, disaster, regulators)

-

professional bodies (medical associations, engineers)

-

community leaders and trusted intermediaries

-

frontline staff who interact with the public daily

-

credible media voices briefed with accurate information

The messenger should match the audience’s trust landscape.

Step 6: Deploy corrections through trusted channels

Use channels based on:

-

speed and reach

-

trust and access

-

relevance to affected groups

Options include:

-

TV/radio public announcements

-

press briefings with Q&A

-

targeted digital ads for high-risk communities

-

SMS alerts for urgent safety guidance

-

community networks and local leaders

-

frontline institutions (clinics, schools, local offices)

Step 7: Monitor, adapt, and reinforce

After response:

-

track whether rumor volume decreases

-

identify new variants of the misinformation

-

note what questions the public is asking

-

update FAQs and clarify points of confusion

Misinformation is rarely a one-time event. It mutates. Governments must adapt.

Pre-Bunking vs Debunking: What Governments Should Do (and When)

Pre-bunking (prevention)

Pre-bunking means preparing the public before misinformation spreads widely by:

-

explaining likely false claims ahead of time

-

clarifying what misinformation patterns look like

-

providing clear reference sources early

-

building public “information hygiene” habits

Pre-bunking is most effective:

-

before reforms are announced

-

early in emerging risks

-

ahead of elections or sensitive policy cycles

-

when you know predictable rumors will appear

Debunking (correction)

Debunking is necessary when harmful misinformation is already spreading.

But debunking must be careful:

-

don’t repeat false claims extensively

-

don’t debate conspiracies endlessly

-

focus on safety, clarity, and verified guidance

In many situations, a combination works best:

-

pre-bunk with “what to expect” and “where to verify”

-

debunk selectively when harm and spread justify it

Managing Misinformation During Crises and Reforms

During crises

Crisis misinformation spreads faster because fear is high and facts evolve quickly.

Best practices:

-

communicate early and regularly

-

acknowledge uncertainty

-

provide clear safety guidance

-

maintain a consistent update cadence

-

coordinate across agencies to prevent contradictions

-

use experts and trusted messengers

During reforms

Reform misinformation often targets:

-

fairness narratives (“they’re stealing from you”)

-

hidden cost narratives (“this is a tax”)

-

foreign influence narratives (“this was forced on us”)

-

corruption narratives (“this benefits elites”)

Best practices:

-

explain trade-offs transparently

-

publish safeguards and accountability mechanisms

-

show the implementation pathway clearly

-

engage stakeholder groups early

-

correct false claims quickly with calm, evidence-based explanations

Misinformation in Low-Trust and Polarized Environments

In polarized environments, corrections can backfire if they appear partisan or dismissive.

Best practices include:

-

use neutral language and avoid attacking opponents publicly

-

focus on shared public-interest outcomes (safety, fairness, stability)

-

rely more on trusted intermediaries and professional validators

-

avoid blame and shaming of citizens

-

listen actively and adapt messaging based on community feedback

-

maintain consistency and restraint (don’t chase every rumor)

In low-trust contexts, the goal is not to “win debates.” It is to maintain calm and enable correct action.

Measurement: How Governments Know If They’re Succeeding

Useful indicators include:

-

rumor volume and velocity (how fast it spreads)

-

reach into priority audiences

-

public understanding (rapid surveys, hotline patterns)

-

changes in behavior compliance (uptake, adherence to guidance)

-

sentiment and trust signals (media framing, community feedback)

-

misinformation mutation patterns (new variants emerging)

Measurement should lead to action:

-

update FAQs

-

refine messages

-

change messenger strategy

-

adjust channel mix

-

improve service readiness if misinformation is driven by poor experience

Institutionalizing Misinformation Management

The strongest governments build misinformation resilience into systems:

-

assign roles and responsibilities (who monitors, who approves, who responds)

-

integrate misinformation monitoring into crisis and risk communication plans

-

create rapid approval pathways for corrections

-

train spokespeople and frontline staff

-

build relationships with credible media outlets and community intermediaries

-

maintain source-of-truth infrastructure (web pages, hotlines, update cadence)

-

document lessons learned after incidents to build institutional memory

Misinformation management should not be a panic response. It should be a prepared capability.

Ethical Boundaries and Democratic Safeguards

A critical distinction must be preserved:

Managing misinformation is not the same as censoring disagreement.

Good practice includes:

-

transparency about what is being corrected and why

-

focusing on harmful false claims that affect safety and public outcomes

-

avoiding suppression of legitimate criticism or debate

-

ensuring proportionality in responses

-

maintaining public confidence through credible, evidence-based communication

Governments build trust when they correct falsehoods while respecting democratic discourse.

Conclusion: Managing Misinformation Is About Protecting Trust

Misinformation and disinformation thrive where trust is weak, uncertainty is high, and official information is delayed or unclear. Governments cannot solve this challenge through denial, defensiveness, or reactive fact-checking alone.

The most effective approach is strategic and systemic:

-

communicate early and consistently

-

be transparent about uncertainty

-

provide clear, actionable guidance

-

correct without amplifying

-

use trusted messengers and channels

-

monitor, adapt, and institutionalize capability

Governments counter misinformation most effectively not by suppressing speech, but by communicating clearly, consistently, and credibly in the public interest—protecting public safety, supporting policy implementation, and preserving institutional legitimacy.