Crises are inevitable in government. A flood displaces communities. A public health threat spreads uncertainty. A data breach exposes sensitive systems. A policy reform triggers backlash. An allegation—true or false—goes viral overnight.

In these moments, the public doesn’t just judge what happened. They judge what government does next—and how clearly, quickly, and credibly it communicates. Often, the most damaging consequences are not caused by the crisis itself, but by the communication vacuum that follows: silence, contradictions, defensiveness, misinformation, and confusion.

That’s why crisis communication isn’t “PR.” It’s a governance function that protects public safety, supports coordination, and preserves institutional legitimacy. This guide outlines a practical framework for governments to prepare before a crisis, respond in real time, and protect trust during and after disruption.

Why Crisis Communication Is a Governance Imperative

In a crisis, people urgently need four things:

-

Clarity: What is happening?

-

Credibility: Who should we trust?

-

Direction: What should we do now?

-

Reassurance: Is leadership present and acting in the public interest?

If government communication fails to provide these quickly, the public will seek them elsewhere. That “elsewhere” may be informal networks, rumor, or politically motivated narratives.

When crisis communication is handled well, it can:

-

reduce panic and harmful behavior

-

increase public cooperation and compliance

-

protect vulnerable communities with timely instructions

-

prevent misinformation from dominating the information environment

-

demonstrate competence and accountability

-

preserve long-term trust in institutions

When it is handled poorly, it can:

-

accelerate rumor and confusion

-

increase hostility, backlash, and polarization

-

undermine compliance with safety instructions

-

damage institutional legitimacy for years

A crisis is not only an operational challenge. It is a public trust test.

What Is Crisis Communication in the Public Sector?

A clear definition

Public-sector crisis communication is the structured process through which governments and public institutions inform, guide, and reassure the public and stakeholders during high-risk, high-uncertainty events—while supporting public safety, continuity of services, and institutional legitimacy.

It includes:

-

early acknowledgement and updates

-

risk and safety instructions

-

coordination across agencies

-

rumor management and misinformation response

-

internal alignment for frontline delivery

-

recovery messaging and accountability

What makes public-sector crisis communication different

Government crisis communication differs from corporate crisis communication in important ways:

-

Public safety consequences: Poor messaging can literally cost lives.

-

Legal and ethical obligations: Accuracy, privacy, equity, accessibility, neutrality.

-

Public accountability: Decisions face scrutiny from media, opposition, civil society, and international partners.

-

Multiple institutions speaking: Ministries, agencies, local authorities, police, health services—often without a single unified voice.

-

Complex stakeholder landscape: Citizens, frontline staff, unions, businesses, donors, embassies, NGOs, community leaders.

-

Trust dynamics: Many publics may already distrust institutions, making crisis messaging harder to land.

Because the stakes are higher, governments need systems, not improvisation.

Types of Crises Governments Commonly Face

Crisis frameworks work best when they are grounded in realistic scenarios. Governments most commonly face five crisis categories:

1) Health and public safety emergencies

-

disease outbreaks, pandemics

-

food/water contamination

-

industrial accidents, chemical exposure

-

public violence incidents

Communication risk: fear, rumors, stigma, low compliance.

2) Natural disasters and climate-related events

-

floods, landslides, cyclones, drought

-

heat emergencies and wildfire risks

-

earthquakes and infrastructure damage

Communication risk: urgent instructions, evacuations, resource coordination.

3) Infrastructure and service failures

-

power outages, fuel supply disruptions

-

transport failures, port closures

-

telecom failures

-

digital system outages (IDs, payments, service portals)

Communication risk: confusion, anger, cascading misinformation.

4) Social and political crises

-

protests, unrest, communal tensions

-

policy backlash and reform resistance

-

high-profile incidents with political sensitivity

Communication risk: polarization, escalation, legitimacy challenges.

5) Institutional and reputational crises

-

corruption allegations, misconduct claims

-

procurement failures

-

data breaches

-

leadership scandals

Communication risk: credibility collapse, perceived coverups, international scrutiny.

A government’s crisis communication capability must be flexible enough to handle all of these—because crises rarely arrive as “clean” categories.

Why Governments Often Fail at Crisis Communication

Most crisis communication failures are predictable. They happen because governments default to habits that worked in stable times but collapse under uncertainty.

1) Delayed communication

Many institutions wait for “perfect information.” But crises evolve faster than approvals. Silence creates a vacuum, and vacuums get filled by speculation.

Better principle: communicate early with what you know, what you don’t know, and what you’re doing next.

2) Inconsistent or contradictory messaging

When multiple agencies speak without coordination, the public hears:

-

different numbers

-

different instructions

-

different explanations

-

different tones

Contradictions signal confusion inside government—and trust falls quickly.

3) Defensive or overly technical language

In a crisis, institutional language often becomes:

-

legalistic (“in accordance with…”)

-

procedural (“an inquiry has been initiated…”)

-

self-protective (“we categorically deny…”)

But the public is asking: “Am I safe? What should I do? What happens next?”

4) Lack of preparedness and unclear roles

Without predefined roles, governments face:

-

spokesperson confusion

-

slow approvals

-

unclear ownership of updates

-

leaders speaking without technical alignment

Crisis communication cannot be invented during a crisis. It must be trained and rehearsed.

5) Failure to address emotion and fear

Facts alone are not enough. Fear changes how people process information. If communication ignores public anxiety, even accurate information can be rejected.

Empathy is not weakness. It is a trust multiplier.

The Strategic Role of Crisis Communication in Protecting Trust

Crisis communication should be understood as a tool that protects three things:

1) Public safety

Clear instructions can reduce harm:

-

where to go

-

what to avoid

-

how to access services

-

what to do if conditions change

2) Public cooperation

Most crisis responses require compliance:

-

evacuation orders

-

health guidance

-

reporting procedures

-

controlled access to sensitive areas

-

adherence to service changes

Communication is what turns policy into cooperative action.

3) Institutional legitimacy

Crises create narratives:

-

“They were transparent.”

-

“They hid the truth.”

-

“They were competent.”

-

“They were confused.”

-

“They cared.”

-

“They didn’t.”

These narratives endure long after the crisis ends. Governments protect trust by choosing credibility over control.

Preparing for a Crisis: What Governments Must Do Before It Happens

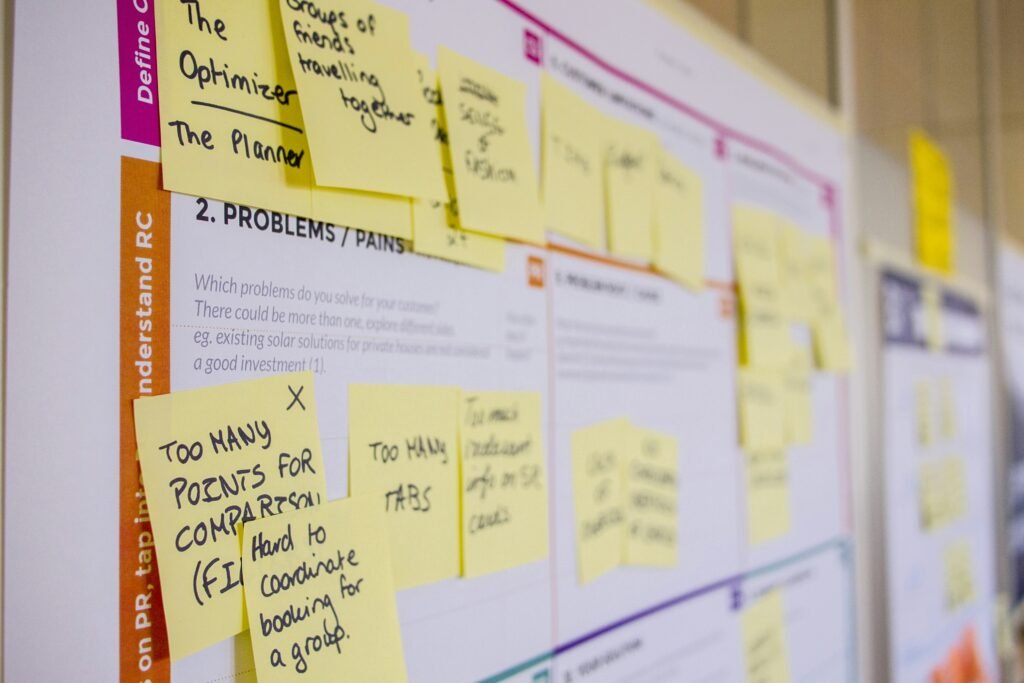

The strongest crisis communication is built before the crisis. Preparation reduces response time, improves consistency, and protects leadership from improvising under pressure.

A. Map likely crisis scenarios

A crisis map identifies:

-

most probable crisis types for your context

-

likely triggers

-

operational vulnerabilities

-

reputational risks

-

affected populations and regions

A practical method:

-

high probability / high impact risks first

-

anticipate “compound crises” (e.g., flooding + power outage + misinformation)

B. Build a crisis communication protocol

A crisis protocol should clarify:

1) Decision and approval flow

-

who can approve initial statements

-

maximum approval time limits (crises cannot wait days)

-

what can be pre-approved

2) Spokesperson roles

-

who speaks on what (technical vs leadership vs local authority)

-

backup spokespersons if primary spokespeople are unavailable

3) Update cadence

-

how often updates are issued

-

where updates will be published as the official reference point

4) Coordination mechanism

-

how ministries and agencies align messaging

-

shared “message architecture” and fact sheets

C. Prepare message frameworks and templates

Pre-approved materials save critical hours:

-

“holding statement” templates (acknowledge, commit to updates)

-

safety instruction templates

-

FAQ templates for common scenarios

-

myth-busting templates

-

social media copy structures

-

press briefing outlines

Templates should include:

-

plain language

-

local-language versions where relevant

-

accessibility considerations

D. Train spokespersons and leadership

Training should cover:

-

speaking clearly under pressure

-

empathy and tone

-

avoiding speculation

-

bridging to key messages

-

handling hostile questioning

-

communicating uncertainty honestly

Spokespersons should practice with simulations, not theory.

E. Set up monitoring and early warning systems

Crisis communication needs early detection:

-

media monitoring for emerging issues

-

social listening for rumor and sentiment shifts

-

frontline reporting loops (clinics, police, local offices)

-

community leader feedback

Monitoring is not only about “PR risk.” It is about detecting misinformation that can cause harm.

Responding During a Crisis: A Real-Time Communication Framework

When crisis hits, governments need a repeatable response model. Below is a practical step-by-step structure.

Step 1: Speak early and acknowledge the situation

The first statement matters because it shapes the narrative.

An effective early message includes:

-

what happened (known facts only)

-

what is being done immediately

-

what the public should do now (if applicable)

-

when the next update will be provided

-

where verified information will be posted

Key principle: acknowledge uncertainty without speculation.

-

“We are verifying…” is better than silence.

-

“We will update at 6 pm” builds predictability.

Step 2: Prioritize public safety and clear action

Most crisis communications should answer:

-

Who is affected?

-

What is the risk?

-

What should people do now?

-

What should people avoid?

-

Where should people go for assistance?

-

What resources are available?

Action guidance must be:

-

concrete (“boil water for 3 minutes”)

-

accessible (language, literacy)

-

consistent across channels

Step 3: Show empathy and human leadership

Empathy increases credibility. It signals that government understands real impact:

-

loss, fear, disruption, uncertainty

Empathy should be:

-

sincere

-

concise

-

followed by action steps

Avoid performative language. The public can detect it quickly.

Step 4: Maintain consistency across institutions

Coordination prevents contradictions. Governments should establish:

-

a central fact sheet updated continuously

-

shared key messages across agencies

-

a unified terminology guide (avoid shifting labels)

If multiple institutions must communicate, define:

-

who leads daily updates

-

who supports with technical briefings

-

how local authorities mirror national guidance

Step 5: Manage misinformation and rumors

Misinformation spreads fastest when:

-

facts are unclear

-

trust is low

-

fear is high

-

official updates are delayed

Practical rumor-response principles:

-

correct quickly

-

repeat the true information more than the false claim

-

use simple language

-

use trusted messengers

-

publish “verified facts” hubs on official platforms

-

avoid amplifying fringe rumors unless they are harmful and widespread

Rumor management is not optional in modern crises—it is a core response task.

Step 6: Use the right channels at the right time

Crisis channels should be selected based on:

-

speed

-

trust

-

access

-

reliability under stress

Most governments need a mix of:

-

TV/radio for mass reach and legitimacy

-

social media for rapid updates and rumor response

-

SMS alerts for urgent instructions

-

websites/portals as the “single source of truth”

-

community networks for low-access populations

-

press briefings for narrative clarity

Channel integration is crucial. Mixed messages across platforms destroy confidence.

Leadership, Visibility, and Credibility in Crisis Communication

In government crises, leadership visibility is a balancing act.

Why leadership presence matters

During uncertainty, public confidence depends on whether leaders appear:

-

competent

-

present

-

accountable

-

coordinated

But leadership should not replace technical credibility.

Who should speak—and when

A strong model often includes:

-

technical experts for facts, risk, and guidance

-

political leadership for accountability, mobilization, and reassurance

-

local authorities for location-specific instructions and support access

Risks to avoid

-

leaders speaking too often without new information (fatigue, contradictions)

-

leaders becoming defensive or political

-

experts speaking without empathy

-

competing spokespeople with inconsistent language

Credibility is built through consistency, restraint, and clarity—not volume.

Crisis Communication in Low-Trust and High-Risk Contexts

When trust is weak, crisis communication becomes harder—but also more important.

Key strategies:

-

use trusted intermediaries (community leaders, professional bodies, local media)

-

demonstrate transparency quickly (“what we know, what we don’t”)

-

prioritize action guidance over reassurance rhetoric

-

avoid blaming citizens or “scolding” language

-

maintain neutrality to prevent polarization

-

listen actively and adapt messages based on feedback

In polarized environments, communication must reduce escalation and create stability, not win arguments.

Measuring Crisis Communication Effectiveness

Even in a crisis, measurement matters—not for vanity, but for correction.

Useful indicators include:

-

public understanding (rapid polls, hotline question trends)

-

compliance signals (service uptake, evacuation adherence)

-

sentiment and trust indicators (qualitative monitoring, digital trends)

-

misinformation volume and spread (rumor tracking)

-

media accuracy (are key facts being reported correctly?)

-

equity reach (are vulnerable groups receiving guidance?)

Measurement enables the most important crisis capability: adaptation.

Post-Crisis Communication: Recovery, Accountability, and Learning

The crisis does not end when the immediate threat stabilizes. Public trust is often won or lost in the recovery phase.

Post-crisis communication should include:

-

recovery timelines and service restoration updates

-

clear next steps for affected communities

-

transparency about investigations or assessments

-

acknowledgment of lessons learned

-

visible improvements to prevent recurrence

-

recognition of frontline workers and community cooperation

Accountability is not only legal. It is communicative. People want to know:

-

What happened?

-

Why?

-

What will change?

Avoid the temptation to “move on” too quickly. Closure builds trust.

Building Long-Term Crisis Communication Capacity

Crisis communication capability should be institutionalized through:

-

crisis playbooks and updated templates

-

routine simulations and drills

-

spokesperson training refreshers

-

monitoring systems and rumor-response protocols

-

cross-agency coordination structures

-

documentation of lessons learned (“institutional memory”)

Many governments relearn the same crisis lessons repeatedly because knowledge is not embedded into systems. Institutionalizing learning is one of the most valuable long-term investments.

Conclusion: Crisis Communication as a Test of Governance

Crises are inevitable. Communication failure is not.

Governments protect trust in moments of crisis not by controlling narratives, but by communicating clearly, honestly, and decisively in the public interest. Preparation, coordination, empathy, and credible guidance are what prevent confusion from becoming chaos.

A strong crisis communication system helps governments:

-

protect public safety

-

mobilize cooperation

-

limit misinformation damage

-

preserve legitimacy under pressure

-

recover with accountability and resilience

In the end, crisis communication is a test of governance itself—and the governments that pass it are those that prepare before the crisis arrives.